The Legend of the Dragon (Part 2)

(Minghui.org) (Continued from Part 1)

There are many stories about Yu the Great, a legendary king in ancient China known for controlling water. According to Huainanzi, Yu the Great once transformed into a gigantic bear to cut through Xuanyuan Mountain. When he was surveying southern China, Yu the Great was sailing down a river when a yellow dragon appeared. The other people in the boat were scared to death, but Yu the Great said, “Given a mission by the divine, I have been working hard to serve the people. Being here gives me time to fulfill my mission and death means returning to where I came from. There is nothing that can disturb my mind.” The dragon then left.

Many stories and cultural relics associated with dragons can be found throughout Chinese culture. Depictions of dragons appear everywhere, from sculptures to drawings, from utensils to adornments and banners. While some people take dragons as fictional creatures in mythology, it’s intriguing to wonder how the ancients could have come up with such a vivid and coherent image of a dragon.

6,000-Year-Old Relics

Long ago during the construction of a water re-routing project, a seven-meter-long dragon pattern was unearthed in a village in Huangmei County, Hubei Province.

Paved with cobblestones, the pattern shows a dragon with four claws like a qilin (also known as a kirin, a legendary creature), a pair of horns like a deer, scales, and a tail. The pattern was very vivid, and it caught the attention of archaeologists as well as biologists. It’s been estimated that the pattern was created at least 6,000 years ago.

Hongshan Culture

Another example was the Hongshan culture in Chifeng City, Inner Mongolia. In 1971, a jade dragon was unearthed. It was the oldest jade dragon archaeologists had ever found.

This artwork is 60 cm (about 24 inches) long and 2.3 cm (about one inch) in diameter. The head has eyes, a nose, a mouth, and a beard. The mane on the back of the dragon is decorated even more vividly. Other jade artworks crafted in a similar style have been unearthed in Inner Mongolia and nearby Liaoning Province.

While the above findings are about ancient relics, the following incidents from modern China might offer more insights into the existence of dragons.

A Fallen Dragon

One incident occurred in Yingkou City, Liaoning Province, in the summer of 1934. It had been raining for over a month and a reed pond was flooded. A local resident smelled something strange in the pond. When he and others investigated, they discovered a gigantic creature that appeared to be dying.

Xiao Yuqin, an elderly woman in Yingkou, was only nine years old back then. In 2004 she recalled that she was standing on the back of a horse supported by her father when she saw the creature. She saw the dragon’s eyes were half closed and its tail was curled. It had two front claws, just like the image of a dragon people usually describe.

Considering the dragon an auspicious creature, the locals tried to save it. Some built a canopy to keep the sunlight off of it, while others kept pouring water over it. This went on for a few days until the creature disappeared mysteriously. Over three weeks later, however, people spotted the dragon somewhere in Yingkou, and by then it had died.

Another elderly person, Yang Shunyi, told the Yingkou History Office in 2004 what he saw back then. He even showed the officials where the dragon had died. “There were many triangular-shaped bones on the ground, over 100 of them. The creature also had one or two horns.”

Locals at the time believed it was a fallen dragon, that heaven might have punished it and struck it with lightning before it fell into the pond.

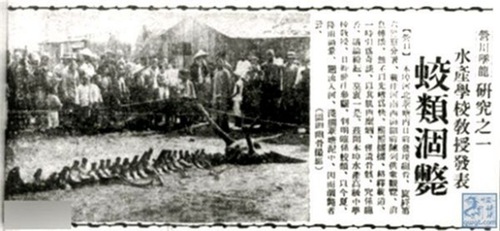

According to an article titled “Dragon Dies Due to Dehydration” in the Shengjing Times on August 14, 1934, the bones of the dragon were transferred to Hebei Province and put on public display. Many people were interested in it.

Report on the dragon in the Shengjing Times on August 14, 1934.

Report on the dragon in the Shengjing Times on August 14, 1934.

The Mysterious Dragon Bones

On June 16, 2004, Sun Zhengren, 81, of Yingkou brought a box with five pieces of bones to the Yingkou History Office. He said that they were dragon bones that he’d collected in 1934 when he was 11.

Han Xiaodong, the deputy director of the office, and other staff members were so curious that they looked for and found the August 14, 1934, Shengjing Times article on the dragon.

Shengjing Times alsoreported that the dragon had two horns on its head and four claws. The dragon had dug itself a pit 17 meters (about 56 feet) long and seven meters (about 23 feet) wide. Marks left by the claws scratching could be clearly seen. Apparently, the dragon had struggled before it died.

The report also cited Li Binsheng, a cartoonist from Beijing, who said that he and two siblings saw the dragon back then. “I was 10 at the time and the creature was surrounded by anchors and ropes to prevent visitors from getting close,” he recalled. “It was about 10 meters (11 yards) long. The backbone curved up in the middle—not like a fish. There were horns on its head different from any sea creature’s.”

When the incident was reported on national TV, CCTV claimed that the bones Sun had brought in were whale bones. But three more elderly people from Yingkou—Cai Shoukang, Huang Zhenfu, and Zhang Shunxi—who had all seen the dragon firsthand, immediately contradicted that assertion.

Cai said he was nine years old at the time and lived near the reed pond where the dragon was found. In addition, he and his friends once saw a dragon in the sky for about 15 seconds on a cloudy day in 1934. The dragon was gray and it moved in the sky like a snake. It was similar to familiar pictures of dragons: two straight horns on its head, a beard, and bulging eyes. The dragon was over 10 meters (about 11 yards) long with scales, four claws like a crocodile, and a tail like a carp.

Cai, Huang, and Zhang all said it was wrong for CCTV to claim the dragon was a whale. Cai wrote to both CCTV and the Beijing Zoo but never heard back.

The CCTV made a follow-up program in 2005. While it didn’t specifically admit to the existence of a dragon, it no longer insisted that the fallen creature was a whale.

A Lost Culture

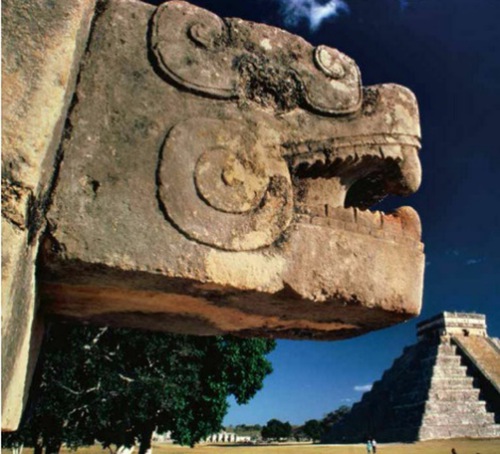

Images of dragons have also appeared in other civilizations. In the Temple of Kukulcan at the Chichén Itzá archaeological site in Mexico, there are two sculptures of the rain god Chaac at the north corner of the pyramid. They look very similar to a dragon, which resonates with the belief in Chinese culture that dragons are in charge of rain.

Like ancient Chinese culture, the Mayan civilization was also very advanced. The Kukulcan Pyramid was about 30 meters (about 33 yards) tall and had 91 stairs on each side. Adding those to the last stair on the top, there were 365 stairs in total, representing the number of days in one year.

The similarity between the Mayan rain god Chaac and the Chinese dragon that is also responsible for rain is evidence of a common thread across cultures. Another common belief across different civilizations is that prehistoric civilizations were once destroyed by floods and that the people of these civilizations are waiting for salvation from the Creator.

Some great scientists have recognized the importance of an open mind. Albert Einstein, for example, once noted that modern science can only prove the existence of something and cannot disprove that something does not exist. “We see a universe marvelously arranged, obeying certain laws, but we understand the laws only dimly,” he also said.

Will mankind ever be able to see dragons and hints from the divine world again? Time will tell.

(The end)