Published: May 9, 2005

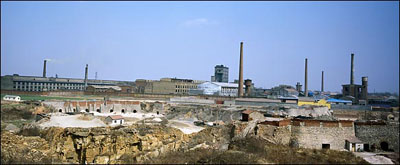

Du Bin for The New York Times

Shandong No. 2 Labor Re-education Camp in Zibo is also a carbonized thermal parts factory. All inmates are expected to do some factory work or manual labor. The camp is one of more than 300 special prisons.

[Since the Chinese communist regime is in power, China's labor re-education system has become a tool for the party to persecute innocent people in each political movement. A New York Times reporter interviewed some Falun Gong practitioners who were imprisoned in China's labor re-education camps. The following is an excerpt of his report entitled, "Issue in China: Many in Jails Without Trial" published on May 9, 2005.-Ed.]

ZIBO, China - For a Chinese government that regularly promises its citizens a society governed by the rule of law, the case of a neatly dressed man named Li is a reminder of what still remains outside the law.

Here in a bleak stretch of eastern China, Mr. Li, 40, spent two years in a prison called Shandong No. 2 Labor Re-education Camp. Mr. Li, who spoke on condition that only his surname be used, and other followers of the banned spiritual group Falun Gong have been jailed here despite never having a lawyer or a trial - rights granted under China's criminal law.

That is because Shandong No. 2 is part of a vast penal system in China that is separate from the judicial system. Falun Gong members are hardly the only inmates. Locked inside more than 300 special prisons are an estimated 300,000 prostitutes, drug users, petty criminals and other political prisoners who have been stripped of any legal rights.

In a nondemocratic country like China, such abuse of legal rights might not seem surprising. But this system, a relic of the Mao era, is presenting a dilemma for a modern Communist Party that faces pressure at home and abroad to change the system yet remains obsessed with security and political control.

The government this year is expected to begin privately considering whether, and how, to change the system.

At the same time, the European Union has stated that for China to achieve one of its most prized diplomatic goals - the lifting of Europe's arms embargo - it needs to make a significant gesture on human rights.

Human rights advocates agree that few gestures would be more significant than abolishing or changing this system, which is known as reform through labor re-education. But unlike releasing a political prisoner, a common Chinese good-will gesture, changing labor re-education could force the Communist Party to give up a major tool it has used to maintain its hold on power.

"It is important for the power holders that a system like labor re-education stay in place," said Gao Zhisheng, a lawyer in Beijing and an advocate of changing the legal system.

The crackdown on Falun Gong followers like Mr. Li is a case in point. [...]

The existence of labor re-education meant the police could sweep up masses of people without the time and complications of court trials. "If they wanted to imprison these tens of thousands of followers through normal judicial processes, it would have been impossible because what these people were doing was not a crime," Mr. Gao said. In fact the government did not approve an anti-cult law aimed at the group until months after the crackdown began.

[...]

The domestic debate is occurring as key members of the European Union this month expressed reluctance to lift the arms embargo by June, as they once had strongly suggested. European officials have emphasized that that they want China to make "concrete" improvements on human rights. One idea that has been suggested is ratifying the United Nations International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

"Pigs will fly before they can ratify with reform through labor re-education in place," said John Kamm, executive director of the Dui Hua Foundation, a group that negotiates the release of political prisoners from China. "It's a violation of every due process right in every human rights law."

Labor re-education camps opened in 1957. The system has become a quick, easy way for the police to imprison people in infractions that violate the social order. Critics say the system gives the police so much latitude that they can arbitrarily choose whether to file criminal charges against someone or simply place that person in labor re-education.

[...]

Conditions and treatment in the more than 300 prisons in the system are said to vary. All inmates are expected to do some type of factory work or manual labor. Some imprisoned intellectuals have described fairly mild conditions, while other people have reported much harsher treatment.

Outside China, Falun Gong is waging an aggressive campaign to publicize its allegations of mistreatment, which the Chinese government has denied. [...]

But there is no question that Falun Gong remains banned in China.

In interviews in China, five Falun Gong followers traveled hundreds of miles to avoid government security agents and described their experiences in labor re-education camps.

Mr. Li arrived in 2000 after spending 10 days in a police holding cell. His family was not notified until he had begun serving a two-year sentence. He said guards often jolted inmates with electric cattle prods to get them to renounce Falun Gong. "The pain was indescribable," he said. "My body jumped in the air."

Two female inmates described repeated humiliations. Menstruating women were shackled standing against a board and then prevented from sleeping or going to the bathroom for several days.

[...]

Mr. Gao, the Beijing lawyer, said Falun Gong followers were still being jailed and labor re-education camps were also now being used to jail some of the petitioners complaining at government offices about corruption or illegal land seizures.

"Unless there are massive structural changes in the way power is organized and allocated in China, there is going to be no change," he said.

Source: http://www.nytimes.com/2005/05/09/international/asia/09china.html

All content published on this website is copyrighted by Minghui.org. Minghui will produce compilations of its online content regularly and on special occasions.