By Xiaodu

(Continued from Part 1)

Part VI: Cangjie’s Creation of Chinese Characters

If Fuxi’s eight trigrams make up the language that the gods use to speak to humans, then Cangjie’s invention of written Chinese forms the language that humans use to speak with other humans. Both languages originate from the nature of the universe, and each serves their own special purpose.

With the trigrams, people could read the course of nature’s progression, enlighten to celestial secrets, and predict fortune or misfortune. Within the characters, people could see the essence of all things in the universe and decipher their inner meanings—for when Cangjie crafted each character, he considered the central traits of what it represented in deciding its form.

Cangjie is said to have been the official historian of the Yellow Emperor, and a native of Xinzheng in Henan Province. The master he served, the Yellow Emperor, is the first of the Five Emperors who established the five millennia of Chinese civilization. The emperor’s reign lasted 100 years, from circa 2,697 B.C. to 2,597 B.C.

According to legend, Cangjie was born with a deity-like appearance and had four eyes. He used all four of these eyes to observe all sorts of animals and objects, and was tasked with forming a language out of his observations to replace the government’s record-keeping system of tying knots.

But as the story goes, it took Cangjie a while to figure out how to complete the Yellow Emperor’s assignment. At the beginning, it was quite a struggle and he didn’t know where to start.

One day, while he was pacing a terrace, thinking hard about how to devise his new language, a phoenix flew over his head. It was holding something in its beak, which it dropped at Cangjie’s feet. Cangjie picked up the object and saw that there was a hoof-print on it. He didn’t recognize the hoof-print, so he asked a local hunter. The hunter told Cangjie that it was the print of a Pixiu, a griffin-like mythical beast.

Cangjie was greatly inspired by the experience and started to create characters by noting down the special characteristics of all things he could perceive. He observed things intently and thoughtfully, with an aim of picking out their innermost nature. Before long, he had compiled a long list of characters for writing. Later generations would build a monument at the terrace where Cangjie saw the phoenix to commemorate his contribution to the Chinese language.

Monument erected in memory of where Cangjie created Chinese characters

Monument erected in memory of where Cangjie created Chinese characters

Wang Anshi (1012–1086 A.D.), a renowned poet, philosopher, court official, and reformist during the Song Dynasty, commented on the kind of deep, metaphysical observation practiced by Cangjie in A Trip to Baochan Mountain:

“The ancients often gained insight by contemplating the universe—mountains and rivers, the vegetation, fish and species of insects, as well as birds and beasts. They were able to do so because they sought both breadth and depth in the scope of their meditations.”

Cangjie was able to use this type of observation to capture the quintessential “shape” of objects. He would start by identifying the object’s defining characteristics through collating his impressions of the object from daily life. He would then start drawing them, creating the first group of Chinese characters: pictograms. For example, the character zhua (爪)for “claw” looks very much like a bird’s foot or an animal’s paw; the character niao (鳥) for “bird ” and chi (齒) for “tooth” also take inspiration from the appearances of the objects they represent.

These pictograms are then combined to form ideographic characters, which are more abstract illustrations of concepts that are a little less straightforward. For instance, the character fei (飛), meaning “flight” or “to fly,” consists of an pictogram of a flying bird on top of the character sheng (升), meaning “to rise.”

The character xiu (休), meaning “to rest,” is made with two components: the ren radical, which is derived from the character ren (人) meaning “person,” and the character mu (木), meaning “wood” or “tree.” In this case, the ideographic character paints a picture of a person leaning against a tree to take a break, but the mu character is used as a radical in plenty of characters to mean wood. Many characters for furniture contain the mu radical.

Another verb example is the character cai (采), which means “to pick.” It is comprised of the zhua (爪)radical on top, indicating a claw, with the character mu (木)on the bottom, showing a hand reaching for a tree to pick fruit.

Ideographic characters can also be used to express adjectives and adverbs as well. The character jian (尖) is made up of the character xiao (小)for “small” atop the character da (大)for “big.” Placing the character bu (不), meaning “not,” on top of the character zheng (正), meaning “correct” gets you the character wai (歪), which means “crooked.” When a forest, lin (林), is set on fire, huo (火), we get the character fen (焚), which means “burning.”

Certain ideographic characters also represent nouns, such as the character xian (仙)for “immortal,” which has the ren (人)radical for “person” on the left and the character shan (山) for “mountain” on the right. This is based on the Chinese belief that immortals and deities like to live in the mountains. Many fantastical places in Chinese legend, such as Mount Kunlun, are located on the loftiest of peaks.

A third class of Chinese characters builds upon the foundation set by ideographs and pictographs—phono-semantic compound characters. These characters are composed of one character that lends itself to the overall character’s pronunciation, along with a radical that connotes the context of its usage. For example, the character lao (姥), meaning “grandma,” places the radical for nü (女), meaning “woman,” beside the character lao (老), which means “old.” The “old” lao (老) within the “grandma” lao (姥) gives readers a clue as to how the latter should be pronounced.

Many Chinese historical texts acknowledge Cangjie as the creator of the Chinese writing system, and many even detail his process. Shuowen Jiezi, an ancient Chinese dictionary,describes the development of the Chinese language like this:

“Cangjie first invented characters based on pictograms; these were called wen (文). He later devised the pictophonetic characters, where the shape and sound complemented each other; these were called zi (字). Pictograms reflect the original characteristics of things, while pictophonetic characters had the ability to proliferate and soon grew in number. When these characters are written on bamboo splits, it was called a book.”

Xunzi, one of the three classical Confucians along with Confucius and Mencius, also wrote about Cangjie in his work. In Jiebi, translated as “Removing the Curtains,” he said:

“There have been many who love to write, but the forms created by Cangjie, the creator of characters, are simply unparalleled—this is because Cangjie achieved oneness of mind [in his creation of the characters.]”

Cangjie indeed treated the creation of characters like a process of meditation, maintaining stillness of mind and purity of intent throughout. He aimed to capture the true nature of all the objects, places, and ideas around him, whether it was through studying forms, collecting traits, experiencing different emotions, or experimenting with concepts. These characters, crafted through his meticulous observation, are then fine-tuned with designated pronunciations and metonymy to bring this true nature to life.

Because Cangjie’s characters are imbued with the true nature of all things, they are connected to the fundamental law of the universe and preserve a link to the divine.

In creating his characters, Cangjie took the simplest and most direct path from meaning to language. The Chinese language he fashioned is perhaps the best in the world for expressing the inner essence of the world’s phenomena and artifacts, and the one that’s perhaps best able to articulate the nuances of the human experience. It is truly a brilliant pearl within the bounty of China’s divinely-inspired culture.

However, it’s not only Cangjie’s characters that have been passed down. His practice of mindful observation has also inspired other parts of Chinese culture, including the doctors of Chinese medicine. Legendary physicians such as Li Shizhen, Hua Tuo, and Bianque have transformed Cangjie’s observation into a powerful medical tool.

Li Shizhen (1518–1593 A.D.) is the author of the Compendium of Materia Medica,the most comprehensive medical encyclopedia in the history of traditional Chinese medicine. The work took him 27 years to complete, during which he observed various plants, animals, and minerals, and compiled his medical experience with each—much like Cangjie did with his surroundings.

Hua Tuo and Bian Que were said to have used observation as a diagnostic tool. They set the precedent for the diagnostic process in traditional Chinese medicine, which would begin with studying the patient’s complexion, feeling their pulse, assessing their smell, and evaluating their behavior before the doctor would ask the patient to describe their symptoms. The thinking was that through this type of meditative observation of the patient’s external form, physicians would be able to descry the internal cause of the patient’s malady. This belief that form and spirit—the external and the internal—are deeply connected is the same principle that Cangjie used to capture the true nature of the objects he observed.

Like many other Chinese legends, there was an aspect of self-cultivation to the stories of Cangjie and these physicians. Their meditation-like observations were a way of perfecting their character, and eventually brought them supernormal abilities when it came to observation.

According to legend, both these physicians and Cangjie had the ability to see through their Third Eye, or “Celestial Eye,” and could see things beyond our reality. This was how Hua Tuo and Bian Que could diagnose accurately even without touching a patient, and how Cangjie was able to evince the quintessence of the world through a few simple lines.

Part VII: Contemporary Usage of Chinese Characters

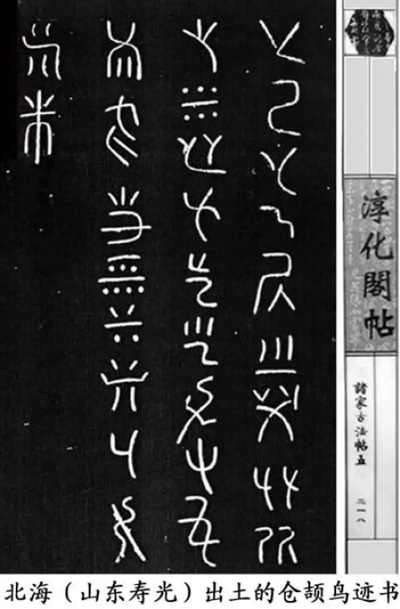

Today’s Chinese characters are the result of continuous evolution and maturation over a long period of time. The oldest known instance of Chinese characters are said to come from the Cangjie Shu, or a legendary piece of Cangjie’s original writing.

Following the Cangjie Shu, scholars have classified the development of written Chinese into five phases: Shang dynasty script, oracle bone script, bronze script, small seal script in the Qin dynasty, and finally to traditional Chinese characters—the same ones still used in Taiwan and Hong Kong to this day.

Throughout this evolution, the characters went from round and elongated to square and angular. The characters we see today, which fit perfectly into squares, are generally assumed to have crystallized in the Han dynasty.

There are about 5,000 commonly-used Chinese characters in today’s lexicon. The Kangxi Dictionary,widely considered the most authoritative Chinese dictionary today, contains over 47,000 characters. Published in 1716 under Emperor Kangxi of the Qing dynasty, it is a testament to both the dynamism and longevity of the Chinese language. In the three centuries since the dictionary’s publication, the language has had to expand significantly to cover an array of novel technologies and ideologies. Yet, the same characters and meanings used by modern sinophones can still be found in the Kangxi Dictionary. Despite having to grow to accommodate these new concepts, the size of the Chinese language actually shrank in terms of the number of utilized characters.

This curious phenomenon is due to how Chinese characters form combinations. Each Chinese character represents one concept or object, but two or more characters can be combined to form words that represent other concepts or objects. For example, the character dian (電), meaning “electricity,” and the character hua (話), meaning “speech,” can be combined to make the word dianhua (電話), which means “telephone.”

So this means even with just 5,000 characters, we can define 5,000 things. And those 5,000 characters can produce over 24 million two-character permutations. Although not every permutation is a valid Chinese word, the calculation gives an idea of the virtually limitless storage capacity of the Chinese language, especially when three-character words, four-character words, and so on are taken into account. Because of this remarkable ability for storing meaning, many linguists consider Chinese to be one of the most precise languages in the word—if not the most precise.

Though spoken Chinese has always had a variety of dialects, written Chinese falls into two broad categories: written vernacular Chinese and Classical Chinese. Today, people primarily use the written vernacular format in both formal and informal settings, with Classical Chinese being treated as more of an art form.

In imperial China, however, Classical Chinese was the standard for official texts. It is more concise than written vernacular Chinese, and allows for a more expansive array of wordplay and rhetorical devices. Due to its economy in using characters, rhyme, antithesis, analogy, and symbolism can easily make their way into the language, which add layers of connotation that gives Classical Chinese a wonderfully expressive and profound quality.

This condensation of meaning is achieved by the logographic nature of the Chinese language, where in addition to giving a word its pronunciation, each character also represents an idea, object, or situation in and of itself. Through language’s ability to shape thought, this habit of speaking volumes using very few words has instilled within the Chinese personality a tendency to communicate through subtext and a sensitivity for the meanings left unsaid.

With a picture to remember for each character, many people may think that Chinese is a difficult language to read and write. Although memorizing characters may be difficult for a learner who’s coming from a language that uses an alphabet, the number of characters actually needed for day-to-day communications are only about 3,000 to 4,000. As long as one overcomes this initial challenge, the rest can be gradually acquired as a learner interacts more and more with Chinese in everyday life.

The pictorial nature of Chinese characters also gave rise to the arts of Chinese calligraphy and typography. In fact, many Chinese believe that one’s handwriting in Chinese is indicative of a person’s inner being—an old Chinese saying even opines that “the writing always mirrors the writer.” Giving someone a compliment about their Chinese handwriting is thus an indirect compliment of their character, so many Chinese have a habit of evaluating calligraphy or handwriting for its inner mien.

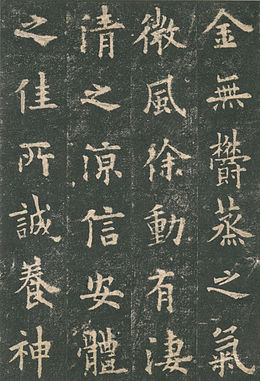

Conversely, Chinese people also believe that practicing one’s calligraphy can also help to refine one’s character. This belief gives rise to different styles of calligraphy, each with their own aesthetic standards, to help people perfect their handwriting.

For example, clerical script, or lishu, is very particular about the “silkworm head and swallow tail” technique—meaning that strokes should begin with heavy pressure and end with light pressure. This technique makes full use of the Chinese calligraphy brush’s flexibility to modulate the thinness and thickness of strokes. Characters written in this style tend to be wider than they are tall, with thicker horizontal strokes and thinner vertical strokes.

Regular script, or kaishu, is another type of calligraphy script. While clerical script was the most popular in the Han dynasty (202 B.C.–220 A.D.), regular script rose to popularity following the dissolution of the Han and has since been the standard. It is the third most popular style of Chinese typography today after the Ming and gothic styles, which are exclusively used for computer-generated text.

Compared to clerical script, regular script characters are more square in shape, and have less variation in stroke thickness. Instead of being symmetrical along the vertical axis like clerical characters, regular characters emphasize the relative proportions of each stroke in relation to the other strokes to achieve balance.

Part VIII: How Simplification Robbed the Chinese Language of Its Soul

Even since the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) rose to power in 1949, it has sought to decimate any aspect of Chinese society that could compete with its own Marxist ideology. This, of course, included the traditional mores of the Chinese people, along with the spirituality that permeated nearly all aspects of Chinese society.

And the Chinese language, as it had existed in 1949, had contained too much of these traditional cultural values. Naturally, it became one of the first targets for the CCP.

Following Josef Stalin’s example in the Soviet Union, Mao Zedong set up the “Language Reform Research Committee of China” in 1952. In December of 1954, the committee was no longer just “researching” language reform; it was dubbed the “Language Reform Committee of China” in preparation for executing its duties. A month later, in January 1955, the committee released a draft of the “Chinese Character Simplification Scheme.” In February that same year, the State Council established the “Committee for the Application of the Chinese Character Simplification Scheme” and began to popularize their newly-minted, “simplified” version of Chinese throughout mainland China.

These simplified Chinese characters lost their original connotations—and are still being criticized to this day by many Chinese people around the world. Some have even made up tongue twisters and rhymes on social media to illustrate the problem with these simplified characters, like the one below:

“Produce without birth: you’ll see nothing get made!A love without heart is no different from hate.How does one cherish whom one does not see?Dive in a well and you’ll find that we’ve strayed.”

The first line refers to the character chan (產), meaning “to produce,” which originally contains the character sheng (生),meaning “birth,” under a component indicating a person, evoking the image of a person giving birth. The simplified version of chan (产) removes the character sheng,which leaves the image of a person producing nothing at all.

The second line is about the character ai (愛), meaning “love.” At the center of the character is the character xin (心), which means “heart.” The simplified character ai (爱)omits the character xin,implying an empty relationship with no substance—for how is anyone supposed to love with no heart?

The third line speaks of the character qin (親), meaning “loved ones.” The right side of this character contains the character jian (見), which means “to see,” signifying that your loved ones were people you saw often. When this character qin got simplified (亲), the entire right side of the original character was taken out, leading to the interesting proposition that you shouldn’t see your loved ones at all.

The final line alludes to one of the more egregious examples of how character simplification distorted the meanings of Chinese. The character jin (進)means “to enter” or “to go forward,” and originally had the radical for transport next to a component based on the character jia (佳), which means “good.” This signifies that as we move forward, we are progressing towards a better state.

However, the simplified version of jin (进)replaces the character jia with the character jing (井), which means “a well.” Needless to say, the image of forward movement as progression into a known dead end is not popular with many Chinese. Many others interpret this character to be a bit of irony: In seeking to “advance” China, the CCP is actually progressing towards its own demise by distancing itself from the traditions and culture that have kept China whole.

Indeed, when we look back at the entire design process of the Chinese language, we can see that it is deeply entwined with the mythos behind the Chinese concept of communication—so much so that in certain parts, the line between history and legend is almost nonexistent. And in nearly all aspects of Chinese language and communication is the subtle, yet strong undercurrent of China’s spiritual culture, grounded in the belief that attuning one’s own character to the universe’s law is a road to the divine. This culture has helped Chinese people maintain harmonious relationships with each other and work out societal conflicts for thousands of years.

Yet the CCP, with its state-enforced atheism, categorically denies the existence of the divine—let alone any kind of universal law. Its faith in social darwinism has caused it to lead the Chinese people in a race to the bottom regarding morality. It endeavors to make the natural environment bend to its will, ruthlessly sacrificing China’s forests and waters at the altar of economic development. It attacks and kills any individuals it dislikes, even among its own ranks, ruling the nation more like the mafia than a political party.

When the spiritual practice Falun Gong appeared in China and reconnected Chinese people with their divine roots, the CCP saw it as a threat to crush. In doing so, it desecrated the values of Truthfulness, Compassion, and Forbearance espoused by the practice—values aligned with universal law—and pushed the Chinese people to oppose these values in abusing Falun Gong practitioners.

Not only are these practitioners insulted and alienated, they are wrongfully arrested and tortured, with many even falling victim to forced organ harvesting. These state-sanctioned crimes against humanity have paved the way for dishonesty, hatred, and belligerence to become even more widespread in Chinese society, pushing Chinese people into a moral abyss.

Just like how its destruction of the traditional Chinese jin turned a bright future into inevitable doom, the CCP’s destruction of China’s traditional values has turned a once-magnificent nation into a cesspool of crime and misery. The people and the elites both suffer under the effects of this immorality: the people from the policies of an unfeeling regime, and the elites from the constant power struggles and betrayals within the CCP organization.

In today’s China, the Chinese legend of creation is less than a fairy tale. But perhaps it’s exactly at a time like this that Chinese people could benefit from the wisdom of the ancestors—from the best things these ancients tried to pass down, from the knowledge they hoped would keep their descendants safe.

And for the rest of us, perhaps China’s story is also a hint to look back at the language, traditions, and values our forefathers left us. Perhaps the universe has always been trying to speak to us, just as the ancient Chinese believed, and it’s just a matter of whether or not we choose to listen.

Category: Traditional Culture